How Wilson Staff Lost Arnold Palmer

The Wilson & Co. could have locked up Arnold Palmer for 10 years if it hadn't been the hubris of its Chairman of the Board.

Wow! What a Sunday on the PGA TOUR. The kind of action and suspense you will find only on the PGA TOUR. Congrats to Rory McIlroy, the perfect champion at the perfect time. Great season for Scotty Scheffler, too. Did you catch the interchange between Rory and Scotty’s dad, wife and mom as he came of the 18th green? Great stuff. The TOUR takes a week off before the Fortinent Championship in Napa, CA. Since there is not a tournament this week, we’re stepping out of our normal lane to highlight a business story from the 1960s and how one of golf’s largest companies lost the biggest star in golf. Scroll down to read about Wilson Sporting Goods and Arnold Palmer.

We love to get feedback! Let us know what you think about Tour Backspin and the stories we tell. Email me at larry@tourbackspin.com.

Listen to The Tour Backspin Show podcast HERE or on Spotify and Apple Podcast.

Congratulations to Bruce Effisimo for correctly answering this week’s WHAT HOLE IS IT? The featured hole was #7 at East Lake Golf Club in Atlanta, GA. Bruce and Owen McClain are running away with the top two spots on the leader board. Submit a “Guest Post” picture for WHAT HOLE IS IT? and if we use it, you’ll win a prize and also be credited with a correct score on the leader board. Send your pic to larry@tourbackspin.com. Scroll down for your chance to win in this week’s WHAT HOLE IS IT?

We’re playing Wilson Staff Trivia this week on the Tour Backspin Quiz. Scroll down to play.

This week’s Vintage Ad keeps the Wilson Staff vibe going. Scroll down to see.

Did you miss a previous newsletter? You can view it HERE. Forward this email to a friend. Was this newsletter forwarded to you? You can sign up HERE.

Okay, we're on the tee, let's get going.

How Wilson Sporting Goods Helped the Development of the Arnold Palmer Golf Company

Arnold Palmer with his Wilson Sporting Goods clubs and bag in 1953

A wild snowstorm is swirling around New York City on a December night in 1960. Arnold Palmer is flying into the city from Florida while Mark McCormick flew in from his home base of Cleveland, OH. McCormick was the founder of the International Management Group, now IMG, whose first client was Palmer. The two stayed at the Plaza Hotel and walked across the street to Trader Vic’s for a dinner meeting. They were meeting to discuss the future of Arnold Palmer in the business world.

The main topic of their meeting was Palmer’s business relationship with Wilson Sporting Goods. Palmer had signed an endorsement agreement with Wilson upon turning professional in 1954. Wilson featured a professional staff that included the most famous names in golf; Sam Snead, Julius Boros, Gene Sarazen, Walter Hagen, Patty Berg, Lloyd Mangrum, and Ed “Porky” Oliver, among many others.

When Palmer signed with McCormick to handle his business deals in late 1959, one of the first things McCormick did was review the contracts that Palmer had signed. The most important of these, the one that McCormick identified as the “meat-and-potatoes contract,” was the endorsement contract with Wilson Sporting Goods.

McCormick was concerned that although Palmer had won the 1958 Masters, along with 14 other PGA tournaments, and had been the PGA Tour leading money winner, the contract he had with Wilson was virtually the same contract he had signed in 1954. He was also concerned that other members of Wilson’s professional staff were being paid more than his client.

The factors that concerned McCormick the most were that the royalty rates were extremely low, it was a world-wide contract meaning that Palmer could not make a dime anywhere without Wilson’s approval, and that any time Arnold endorsed another product, Wilson had to be mentioned in the advertisement. Can you imagine a commercial, or ad, that started with, “Before I hit my Wilson Staff Golf Ball, I light up my L&M Cigarette”? There were many other restrictive clauses in the contract.

“I believe that we can negotiate a far better contract.”

The agreement that Palmer signed in 1954 was a three-year contract that paid Palmer $5,000 a year. That was a significant amount of money when one considers that Palmer made about $20,000 in total winnings on tour in that same period. When the contract came up for renewal in 1957, according to McCormick’s later assessment, Palmer “should have been more cautious.” Instead, on September 25, 1957, Palmer signed a contract with Wilson that renewed the contract, with the same terms, for another three years.

After reviewing Palmer’s contracts, McCormick felt that the Wilson contract was inequitable to Palmer and tried to bring the subject up with his client in early 1960. Palmer was not too interested in the subject.

One day McCormick said to Palmer, “Arnold, you really need to familiarize yourself concerning your position with Wilson. It does not seem to be a very good deal the way things stand. I believe that we can negotiate a far better contract.”

Palmer simply replied, “Oh, let’s talk about it some other time. They are nice people, and I’m sure they are willing to go along with whatever is fair for everybody.”

“There won’t be any trouble, they told me so.”

Palmer explained to McCormick that he had a verbal agreement with the president of Wilson Sporting Goods, Fred Bowman, that Palmer could get out of the agreement at any time if he was unhappy. Also, several people at Wilson Sporting Goods had told Palmer that they had big plans for him concerning a prestigious line of clubs that would be sold in pro shops as opposed to the current Palmer-autographed club line being sold in retail stores. At the time, clubs sold only in pro shops carried much more prestige than those sold in retail stores.

In the weeks that followed, McCormick continued to press Palmer for more details on the Wilson contract. McCormick was concerned that there may have been obligations to Wilson that he was unaware of. Palmer didn’t think so but said, “There may have been something about 1963,” but again reminded McCormick of the verbal agreement with Bowman.

“There won’t be any trouble,” Palmer assured McCormick, “they told me so.”

Palmer then turned his attention to the 1960 tour and played some of the best golf of his career. He won the Palm Springs Desert Classic in early February, added the Texas Open later that month, then the Baton Rouge Open the next week before winning the Masters in April.

Palmer had now exploded as the biggest star on the PGA TOUR and offers came pouring in. Palmer realized that his business life was going to become more complex, whether he liked it or not.

Jack Harkins of the First Flight equipment company approached McCormick and Palmer with the proposal of marketing a premium, pro-shop-only, line of clubs. A main enticement to Palmer was that he would design the clubs himself. Harkins was willing to wait until the end of 1960 when Palmer’s Wilson contract was up, and McCormick had notified Wilson that they were in discussions with Harkins and First Flight.

By mid-May McCormick had worked out the details of a deal with Harkins that included a minimum of $150,000 against royalties and Palmer becoming a director of First Flight. Palmer would also receive stock options that Harkins estimated would be worth a half a million dollars. Palmer would earn bonuses of $5,000 for winning a Masters, or U.S. Open, compared to the $1,000 for the Masters, and $2,000 for the U.S. Open, that Wilson was paying.

McCormick kept Wilson informed on the negotiations, and the offer, from First Flight. This is when McCormick learned that, yes, there was a three-year option that the company could exercise on Palmer’s contract. In effect, this meant that the agreement that Palmer signed in 1954 would apply for nine years.

Palmer figured that his early assurances from his friends at Wilson that he could renegotiate, or even exit from his contract, would either result in a deal equal to the First Flight contract, or that he would be able to exit his contract through a buy-out. Unfortunately, those friends had left the company, or were no longer in positions of power.

“No, we would not.”

Right after the Tournament of Champions in early May, McCormick and Palmer met with the Wilson executives in Chicago. The executives assured Palmer of all the great things they had planned for an Arnold Palmer line of golf equipment and how Palmer was going to make a fortune with Wilson.

Finally, McCormick asked Bill Holmes, the new president of Wilson a key question:

“If Arnold requested a release from his Wilson contract based on the assurances given to him by Wilson officials some time back,” McCormick began, “would you grant the release to him?” After a long, awkward silence, Holmes replied, “No, we would not.”

Holmes then suggested that the contract be renegotiated, a new contract that would be long-term, one for 10 years. Palmer was amenable to this, and the parties shook hands, and the meeting broke up.

McCormick started drafting a new contract while Palmer returned to the tour and promptly won the 1960 U.S. Open at Cherry Hills in Denver, CO. becoming more than just a hot commodity, he became a legend.

McCormick slowly made progress on the new contract that included an increase in royalty payments and the elimination of the restrictive endorsement clauses. McCormick also requested a clause that would defer Palmer’s income into the future and a split-dollar life insurance plan. Wilson agreed to these terms.

“There is even a better way. You could follow Ben Hogan’s example and set up your own company. You are that big.”

This brings us to the dinner at Trader Vic’s in Manhattan on that snowy night in December depicted in this week’s opening. At that meeting, McCormick told Palmer that he thought he was taking a much too conservative path with the Wilson contract. He explained that Palmer had a rare opportunity to make the kind of big money that the likes of Byron Nelson and Ben Hogan never had the chance of making.

McCormick explained that Palmer could make more money than even the First Flight deal offered.

“There is even a better way. You could follow Ben Hogan’s example and set up your own company. You are that big.”

Palmer listened, but in the end, he demurred as he felt a loyalty to Wilson.

“I realize I could probably make a lot more money going some other route, but I’d feel more comfortable not turning my back on them. I’d appreciate it if you would go along with them and try to work it out.”

Okay. The decision had been made and, for better or worse, Palmer would remain with Wilson.

With the contract approved by the lesser executives at Wilson Sporting Goods, McCormick took the agreement to the new chairman of the board at Wilson & Co., the meat-packing giant that Wilson Sporting Goods was a small subsidiary of. The new chairman was the autocratic Judge James D. Cooney. The judge took one look at the agreement and vehemently opposed the deferred-income provision as well as the split-dollar life insurance provision. Even the executives at Wilson & Co. did not enjoy benefits such as these. Besides, didn’t Wilson already have a contract, through 1963, with this fellow Palmer?

By February, McCormick and Palmer had received the news that the new contract had been rejected and the two men immediately began making plans to start the Arnold Palmer Golf Company which would sell Palmer’s own clubs.

In order to buy-out the Wilson contract McCormick and Palmer made the offer to repay all money (estimated to be $75,000) that Wilson had paid Palmer since they entered the original contract. They also offered to purchase from Wilson any existing inventory of Arnold Palmer clubs and balls and that they would reimburse Wilson for any amount which the sale of Palmer pro-only clubs and balls damaged the sale of Wilson’s Palmer-endorsed clubs. They bent over backwards to make a good-faith offer to Wilson that would alleviate any damage that Palmer’s departure might incur.

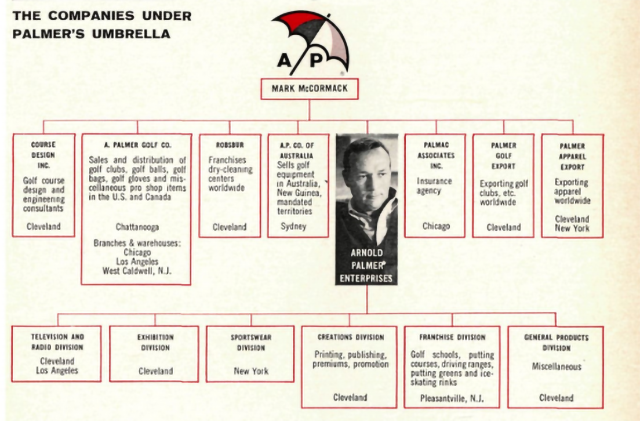

Wilson said no. Wilson was making Palmer wait until the end of its option—October 1963—before they would release him from the contract. Upon hearing this, Palmer no longer felt any loyalty to the company. From that day forward, Palmer has been in big business, primarily with the Arnold Palmer Golf Company, but also with a wide-ranging collection of businesses (see chart).

As much as Palmer desired a long-term relationship with Wilson, even eschewing the large amount of money that he could have made elsewhere, it was an intransigent Wilson executive who pushed him out the door. The result was the creation of the largest business empire by a sports star up to that point in history.

Wilson remained a force in professional golf with the endorsement of players and its Wilson Staff line of clubs through the 1970s and early 1980s. The Wilson line of sporting goods was sold to Pepsico, the beverage giant based in New York, in 1970. Pepsico focused on the sale of boxed sets of golf clubs to large retailers and has never quite recaptured the esteem that it once held amongst the professionals on the PGA TOUR.

The Arnold Palmer business empire circa 1967 (photo: Sports Illustrated)

This week’s Bonus Story is autobiographical. How I was both lucky and stupid.

Be sure to checkout Breaking Up Is Hard To Do, our playlist this week in honor of Wilson Sporting Goods and Arnold Palmer going their separate ways. Listen HERE.

Please help us grow by forwarding this email to a friend who would enjoy it. Thanks.

Enjoy!

Larry Baush

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube

Tour Backspin Playlist

Thanks for reading! Please let your family, friends and colleagues know they

can sign up for email delivery of this free newsletter through this link.

WHAT HOLE IS IT?

Are you on the leader board?

Tour Backspin Quiz | Wilson Staff Trivia

What driver did Sam Snead play for 30 years while on the Wilson Sporting Goods staff?

Answer below

Bonus Story

Bonus Story

I walked into an antique store in downtown Kent, WA, with some buddies when I was around 16 years old. Inside there was an old wooden barrel with some old golf clubs in it. One of the clubs was a putter that was labeled “Wilson Designed by Arnold Palmer” and had a price tag around $10. That equaled two loops as a caddy, so it wasn’t exactly cheap.

I pulled the putter out, held it in my putting stance, and liked the look and feel of it. The putter is a flanged-back model, like a George Low or a MacGregor Tommy Armour.

I think I had to borrow a few bucks from one of my friends, but I bought the putter and used it for years before learning a little something about it. Imagine my surprise when I learned the value of the putter. The putter became somewhat rare after Palmer left Wilson in 1963 to start the Arnold Palmer Golf Company. Wilson changed the name of this model to 8802 and Ben Crenshaw went on to make the 8802 famous by using it to win the 1995 Masters. Today there are many 8802s from that era that can be found, but not many Designed by Arnold Palmer putters.

The limited amount of Designed by Arnold Palmer putters on the market made the club valuable. I later sold the putter for around $200. Wish I hadn’t done that. If you can find an original (there have been reproductions done over the years) it will cost you around a $1,000.

Blind Shot

Click for something fun. 👀

Tour Backspin Quiz Answer:

Sam Snead played a driver that was made by George Izett, a master club maker located in Ardmore, PA. who made a name for himself in the 1930s and 1940s. Snead bought the driver from Henry Picard at the 1937 L.A. Open for $5.50. Snead won $400 at the L.A. Open, the next week he won the Oakland Open, and the winner’s check of $1,200. He went on to win four more times that year.

He signed a contract to represent Wilson Sporting Goods the next year and to make it appear that he was playing a Wilson driver, the company sent a sole plate and crown decal to Izett. Izett had to do some carving to make the sole plate fit correctly.

Thank you to Pete Trenham, PGA Professional and publisher of the Trenham Golf History Blog for this story.

I'd love to hear your feedback! Email me at larry@tourbackspin.com.